Metacognition and affect in relation to maladaptive mobile phone use among school children

Original Article

Metacognition and affect in relation to maladaptive mobile phone use among school children

Andree,1 Preeti Gupta,2 Sanjay Kumar Munda3

1PhD Scholar, Department of Clinical Psychology, CIP, Ranchi

2Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychology, CIP, Ranchi

3Assistant Professor of Psychiatry, CIP, Ranchi

Address for Correspondence: Email: preetiguptacp@gmail.com

ABSTRACT

Objective: Maladaptive mobile phone use is not uncommon among school children. Recent research has suggested that metacognitions and affect may play a role across the spectrum of addictive behaviours, including problematic use of technological devices. The goal of the present study was to study metacognition and affect among school children with maladaptive mobile phone use during the COVID-19 pandemic. Method: The sample was collected online through google forms from 83 students of classes 7th-9th from two secondary co-ed schools of Ranchi, India. This was an explorative study and data was collected from the school session of 2020-2021. A total of 300 students from class 7th-9th were sent the online link, of which 122 gave consent to participate. Result: The results showed that 68% of school-going children from classes 7th -9th had maladaptive mobile phone use, of which 20% had problematic use and 47.5% had occasional problems. There was a significant relationship between metacognition and affect in children with maladaptive mobile phone use. Positive affect was significantly higher in males as compared to females with maladaptive mobile phone use. Metacognitive impairment positively correlates with negative affect in females with maladaptive mobile phone use compared to males. Conclusion: Although more research is needed to identify the underlying mechanisms, findings suggest a need to sensitize students and educators about the potential academic risks associated with high-frequency mobile phone use.

Keywords: Behaviour addiction, COVID-19 pandemic, metacognition, mobile phone use.

INTRODUCTION

Behavioural addiction or psychological addiction has been defined as “a persistent behavioural pattern characterized by a desire or need to continue the activity which places it outside voluntary control; a tendency to increase the frequency or amount of the activity over time; psychological dependence on the pleasurable effects of the activity, and a detrimental effect on the individual and society” (Grant et al., 2010). Problematic smartphone use can be defined as a heterogeneous and multidimensional phenomenon involving a pattern of dependency related to negative consequences (e.g., difficulty in focusing on daily activities or on an inter- personal encounter due to a constant need to check smartphone notifications) (Choliz, 2012; Riley, 2014). Another concept known as Nomophobia, defined as the “fear of being without your phone;” is an emerging problem of the modern era, as found in a study on mobile phone dependence among students of Indian Medical College (Dixit et al., 2010). Children and adolescents are in a development stage wherein they are vulnerable to problematic smartphone usage because of the presence of stressful events and encounters that, together with poor emotion regulation skills, may lead adole- scents to relieve their negative emotions by excessively using smartphones.12,13 There is an established body of literature in the field of behavioural addictions and a variety of beha- viours have been studied in ways analogous to substance use disorders. However, there is very little literature regarding mobile phone addiction. Moreover, little research has been conducted on smartphone use and its consequences. Metacog- nitions was found to be involved in addictive behaviours, including problems with drinking and smoking (Spada et al., 2013; Nikèeviæ and Spada, 2012), gambling (Spada et al., 2015), problematic gaming (Marino and Spada, 2017), generalized problematic Internet use (Spada et al., 2008), and problematic social media use (Casale, Rugai and Fioravanti, 2018; Marino et al., 2018).

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of mobile phones has increased up to three times in school-going children. This can have a major impact on the behavior of young children. Increased use of mobile phones has also resulted in certain behavioral changes and mental stress in school-going children. Therefore, considering the high rate of smartphone use among Indian adolescents, this area needs to be further explo- red, with a focus on developmental constructs such as cognitive and emotional functioning, so that the best prevention and treatment strategies can be worked out. The objective of the study is to study metacognition and positive and negative affect among school children with maladaptive mobile phone use.

METHODS

Ethical approval was received from the Institutional Ethics Committee and written informed consent was taken from all students’ parents and assent from the students prior to their participation.

Study design and participants

This online exploratory study was carried out in the school session of 2020-2021in two co- ed secondary schools in Kanke, Ranchi, India. The study sample was collected using a purposive sampling method after obtaining informed consent from the principal of the schools. A total of 300 students using a smartphone from class 7th-9th were sent the online link, of which 122 gave consent to participate. 83 students scored 16 and above on the Questionnaire about Expe- riences related to Cell phone (CERM) and were sent the link to other questionnaires to measure the metacognition and affect. Participants with any major psychiatric morbidity, chronic or other significant medical, neurological conditions, or organic disorder and any physical or sensory disability were excluded from the study.

Measures

Socio-Demographic and Clinical Data

Sheet (SDCS): It includes information about age, gender, education, religion, and parents’ occupa- tion along with details about significant family histories of psychiatric disorders, duration of sleep hours, year of starting the use of a smart- phone, time spent with smartphone and purposes of use such as gaming, using social network sites, making phone calls, sending emails and messaging.

CERM (Questionnaire about Experiences related to Cellphone): It is comprised of 10 items, rated for frequency on a four-point scale (Almost never, Sometimes, Often, almost always).

“Problematic use” was defined depending on whether the score from the questionnaire was equal to or above 24 and use with “occasional problems” was based upon a score between 16– 23 for the CERM. Cronbach’s alpha value is 0.80.

Meta-cognitions Questionnaire for Adole- scents (MCQ-A): It is a 30-item measure of metacog- nition for the age group of 12-18 years. As well as a total score, the MCQ-A measures five subscales, including 1) Positive Beliefs (e.g., “Worrying helps me cope”), 2) Uncontrollability and Danger (e.g., “My worrying is bad for me”), 3) Cognitive Confidence (e.g., “I do not trust my memory”), 4) Superstition, Punishment, and Responsibility (SPR; e.g., “It is bad to think certain thoughts”), and 5) Cognitive Self- Consciousness (e.g., “I am constantly aware of my thinking”). Participants indicate how much they agree with each statement on a four-point Likert type scale ranging from 1 (do not agree) to 4 (agree very much). The current study demon- strated adequate internal consistency, with Cronbach alpha coefficients for each scale as fol- lows: Positive Beliefs = .90; Uncontrollability and Danger = .87; Cognitive Confidence = .87; SPR = .77; Cognitive Self Consciousness = .78; and Total score = .92.

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule for Children (PANAS-C): PANAS-C is a 27-item self-report scale based on direct questioning, designed to assess affect or recent experiences of positive and negative affect in children aged 6 to 18 years. instructs youngsters to indicate how often they have felt interested, sad, and so on during the “past few weeks” or “past 2 weeks” on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = very slightly or not at all, 5 = extremely). The PANAS-C has good psychometric properties, with reliability alpha coefficients ranging from .89 to .94 for the two affect scores.

Procedure

A list of secondary schools from the Kanke locality of Ranchi, India having coeducation was made and two co-ed secondary schools were selected randomly, and which gave permission to carry out the online exploratory study. The WhatsApp group for different sections of the class of 7th, 8th, and 9th was used to send an online link to the google form consisting of forms of the questionnaires. A total of 300 students from class 7th-9th were sent the online link, of which 122 gave consent to participate. Based on CERM, the cut-off for the identification of maladap- tive mobile phone use was 24 or higher and 16 or above for occasional problems according to which maladaptive mobile phone use among school children was gauged. 83 children from class 7th-9th were finally taken up for the study and data on socio-demographic, academic performance, and scores on MCQ- A and PANAS-C were received online.

Analysis

Appropriate statistical methods were applied using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Version 25.0). Descriptive statistics were used to calculate the frequency and percent- ages of the socio-demographic variables along with the mean and standard deviation of the clinical variables. Pearson’s correlation was used to find the correlation between the various domains of the clinical variables along with the sociodemo- graphic variables.

RESULTS

On CERM, out of 300 students, 83 (68%) students fulfilled the criteria for maladaptive mobile phone use and were included in the sample. Out of which 25 (20.5%) were children with problematic use and 58 (47.54%) were children with occasional problems. Participants sociodemographic and clinical details are given in table 1. There were 49 (59%) males and 34 (41%) females. The majority of school children are from class 9th (48.1%) followed by 8th (32.5%) and 7th (19.3%). Mostly, their school performance was average (49.4%), and 47% of children performed in the above-average range and 3.6% in the below-average range. The majority of children had no disciplinary action taken against them (85.5%) and 9.6% of children reported disciplinary action being taken more than once and 4.8% of children had disciplinary action taken against them once. The sleep pattern of the majority of children was between 6-8 hours (61.4%) followed by 4-6 hours (19.3%) and more than 8 hours (19.3%). The time spent on a mobile phone was mostly 3-6 hours (49.4%) followed by less than 3 hours (27.7%) and more than 6 hours (22.3%).

The total score on metacognition was above the cut-off for both males and females with the highest being in females (Table 2). The domains of cognitive self-consciousness, negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger and the need to control thoughts were elevated in males.

The domains of lack of cognitive confidence, positive beliefs about worry, cognitive self-con- sciousness, negative beliefs about uncontroll- ability of danger and the need to control thoughts are elevated in females and were more than those in males. However, the scores on these domains are not statistically significant. The scores in the domain of positive affect were more in males as compared to females and were statistically significant (0.048, p < 0.05) while the scores in the domain of negative affect were more in females as compared to males and were not statistically significant.

Table 1

Socio-demographic details and clinical details of School Children with Maladaptive Mobile Phone Use (N=83)

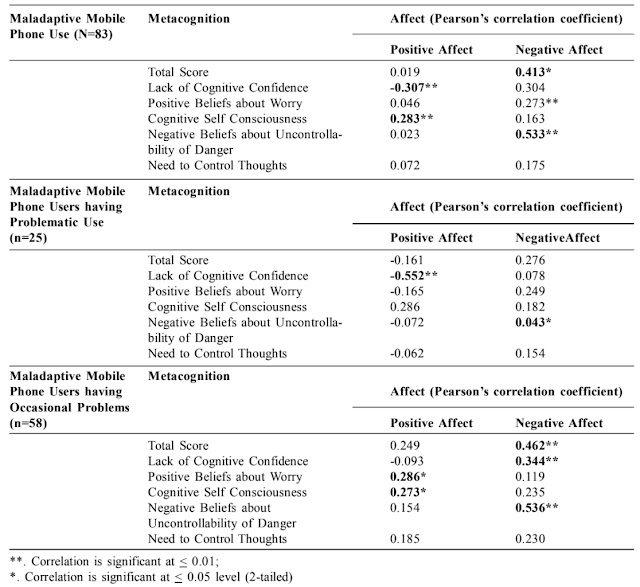

Table 3 presents correlation between metacognition and affect in school children with mala- daptive mobile phone use. In children with maladaptive mobile phone use, the overall score on metacognition was significantly positively correlated with negative affect (0.413, <0.05). The domain of lack of cognitive confidence had a strong negative correlation with positive affect (-0.307, <0.01). The domains of positive belief about worry (0.273, p <0.01) and negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger (0.533, <0.01) had a strong positive correlation with negative affect. The domain of cognitive self-conscious- ness had a strong positive correlation with positive affect (0.283, <0.01). In children with Problematic use, the domain of lack of cognitive confidence had a strong negative correlation with positive affect (-0.552, <0.01). The domain of negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger was positively correlated with negative affect (0.043, <0.05). In children with Occasional problems, the overall score on metacognition was significantly positively correlated with negative affect (0.462, <0.01). The domains of lack of cognitive confidence (0.344, <0.01) and negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger (0.536, <0.01) had a strong positive correlation with positive affect. The domains of positive beliefs about worry (0.286, <0.05) and cognitive self-consciousness (0.273, <0.05) were positively correlated with positive affect.

Table 2

Metacognition and Affect between Male and Female School Children with Maladaptive Mobile Phone use

* Correlation is significant at < 0.05 level significantly positively correlated with negative affect (0.462, <0.01). The domains of lack of cognitive confidence (0.344, <0.01) and negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger (0.536, <0.01) had a strong positive correlation with positive affect. The domains of positive beliefs about worry (0.286, <0.05) and cognitive self-consciousness (0.273, <0.05) were positively correlated with positive affect.

DISCUSSION

Our study focussed to know about metacognition and positive and negative affect among school children with maladaptive mobile phone use. Associations between prolonged mobile phone use and academic performance had been established (Sohn et al., 2019) with prolonged mobile phone use from >2 hours/day on weekdays and >5 hours/day on weekends after controlling for family covariates. However, in the present study despite a higher percentage of maladaptive mobile phone use, very few students were performing below average. The probable reason might be the higher percentage i.e., 47.5% of students were facing occasional problems only as compared to 20.4% of those with problematic use. The majority of participants with maladaptive mobile phone use had no disciplinary action taken against them (85.5%) with 9.6% of children on whom disciplinary action had been taken more than once and 4.8% of participants had disciplinary action taken against them once. The sleep pattern of most children was between 6-8 hours (61.4%) followed by 4-6 hours (19.3%) and more than 8 hours (19.3%). Problematic smartphone use had an association with poor sleep quality (Sohn et al., 2019), however, the mediating effects of reduced sleep duration, insomnia, and depression on the association between prolonged mobile phone use and academic performance have been found small (Liu et al., 2019). The time spent on mobile phone was mostly 3-6 hours (49.4%) followed by less than 3 hours (27.7%) and more than 6 hours (22.3%). This could be because during the pandemic, the classes were being held online for the children which required them to spend more time on the screen.

In the present study, majority of children fulfilled the criteria for maladaptive mobile phone use and were included in the sample out of which 25 (20.5%) were children with problematic use and 58 (47.54%) were children with occasional problems. This was much higher than the percentage previous studies have reported (Sahu, Gandhi and Sharma, 2019; Nikhita, Jadhav and Ajinkya, 2015). Nikhita et al. (2015) reported the prevalence of mobile phone dependence (MPD) as 31.33% in secondary school adolescents in Navi Mumbai, India (Nikhita, Jadhav and Ajinkya, 2015). It could be due to differences in assessment tools used for measuring mobile phone dependence or maladaptive mobile phone use and the large sample size.

Table 3

Correlation between Metacognition and Affect in school children with Maladaptive Mobile Phone Use

Relationship among Metacognition, Affect and Maladaptive Mobile Phone Use

Metacognitive difficulties were significantly associated with the negative affect in the present study as supported by a study by Spada et al. in 2019, (Spada et al., 2008). Their results would seem to suggest that individual differences in metacognition are relevant to understanding the link between perceived stress and negative emotion. Negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger were associated with negative affect in all the groups with overall maladaptive mo- bile phone use and those with problematic use and occasional problems. This may indicate that children who were not able to control their use of mobile phone use had more negative emo- tions. This could be because metacognition manages the cognitive system and emotions related to the cognitions. Good metacognitive skills have protective effects on anxiety disorders, and behavioural addictions. When individuals lose contact with mobile phones, they can have certain thoughts like “I will lose contact with my friends”, “My boredom will not stop if I cannot reach my mobile phone”, or “In a situation of an illness or emergency, I will not be able to reach my family or friends”, “I will lose my connection to the internet, I will not be able to reach the information I need and lose control concerning my assignments.”. These automatic thoughts may increase anxiety and stress levels. Since good metacognitive skills allow the ability to control and correct cognitive errors, they can also provide the management of anxiety and stress caused by these thoughts. Poor metacognitive skills can lead to individuals not being able to regulate their anxiety and stress related to automatic thoughts about losing contact with smartphones as also supported by research by Yavuz, et al. in 2019, (Yavuz et al., 2019).

Lack of cognitive confidence among students with occasional problems with smartphone usage was strongly related to negative affect while it showed a negative relationship with positive affect in those with problematic use. This indica- ted that when lack of cognitive confidence increased, negative affect also increased when problems were perceived occasionally. How- ever, the positive affect was decreasing with an increase in lack of cognitive confidence when problems were perceived as aggravating.

Positive beliefs about worry were related to negative affect in children with maladaptive mobile phone use. However, it was related to positive affect in children with occasional problems and had no relation in the problematic use group. This indicated that the belief that worrying helped them cope resulted in a positive effect in case of occasional problems. Adopting worrying as a strategy to cope with problems might lead to negative affect. However, this finding needs further exploration.

Cognitive Self Consciousness was related to negative affect in children with maladaptive mobile phone use. However, it was related to positive affect in children with occasional problems and had no relation in the problematic use group. This suggested that the degree to which one monitors their thoughts and focuses their attention inwards leads to positive affect in individuals. However, it might lead to negative emotions in individuals who focus their attention and tries to monitor their mind every time. The relation between cognitive self-consciousness and affect had not been observed in research and needed further exploration.

Need to control thoughts had no association with affect which further suggests that the extent to which one believes certain thoughts must be suppressed results in being able to get rid of negative thoughts. However, no research finding was available to support the finding. Research showed that the need to control negative thoughts leads to a paradoxical increase in those thoughts, resulting in negative emotions (Spada, Caselli and Wells, 2009).

The study’s major limitation was that it was exploratory, which could have affected the rela- tionship between the variables. All the scales were self-reporting and administered online which can overestimate or underestimate the real situation of the children. CERM (Questionnaire about Experiences related to Cell phone, Panova and Lleras, 2016) is a new scale and there has been limited research using this scale. The relationship among other sociodemographic variables like academic performance, time spent on the phone, amount of sleep, and purpose of mobile phone use with the clinical variables could be done in future research. Longitudinal study design needs to be framed for further research. This would help get a better understanding. A larger sample may be considered in the future to make the result generalizable. Future studies may include a wider age range of young adolescents as well as late- adolescent children so that the various factors involved in the disorder can be understood better. The various domains of metacognition and its relation to affect could be better explored and gender differences could also be examined. Meta- cognitive factors like lack of cognitive confi- dence, negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger, positive beliefs about worry, and cogni- tive self-consciousness influence an increase in negative emotions in children with maladaptive mobile phone use. Interventions should focus on improving metacognition and increasing pos- itive emotions in students to help children with maladaptive mobile phone use.

CONCLUSION

Maladaptive mobile phone use is not uncommon among school children and adolescents. Metacognitive impairment and negative emotions are seen in children with maladaptive mobile phone use. Few metacognitive domains like lack of cognitive confidence, negative beliefs about uncontrollability of danger, positive beliefs about worry, and cognitive self-consciousness have a positive correlation with negative emotions in children with maladaptive mobile phone use.

Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding: Nil.

REFERENCES

Cartwright-Hatton, S., Mather, A., Illingworth, V., Brocki, J., Harrington, R., Wells, A. (2004). Development and preliminary validation of the Metacognitions Questionnaire — Adolescent Version. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(3), 411-22.

Casale, S., Rugai, L., Fioravanti, G. (2018). Exploring the role of positive metacognitions in explaining the association between the fear of missing out and social media addiction. Addictive behaviors, 85, 83-7.

Choliz, M. (2012). Mobile-phone addiction in adolescence: the test of mobile phone depend- ence (TMD). Progress in health sciences, 2(1), 33-44.

Dixit, S., Shukla, H., Bhagwat, A.K., Bindal, A., Goyal, A., Zaidi, A.K., Shrivastava, A.A. (2010). Study to evaluate mobile phone dependence among students of a medical col- lege and associated hospital in central India. Indian Journal of Community Medicine, 35(2), 339.

Grant, J.E., Potenza, M.N., Weinstein, A., Gorelick, D.A. (2010). Introduction to behavioral addictions. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 36(5), 233-41.

Laurent, J., Catanzaro, S.J., Joiner, T.E., Jr. Rudolph, K.D., Potter, K.I., Lambert, S., Osborne, L., and Gathright, T. (1999). Positive and Negative Affect Scale for Children. Retrieved from PsycTESTS.

Liu, H., Yu, H.L. (2011). The relationship among university students’ mobile phone addiction and mobile phone motive, loneliness. The Journal of Psychological Science, 34, 1453- 7.

Liu, R.D., Wang, J., Gu, D., Ding, Y., Oei, T.P., Hong, W., Zhen, R., Li, Y.M. (2019) The effect of parental phubbing on teenager’s mobile phone dependency behaviors: the me- diation role of subjective norm and dependency intention. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 28, 1059-69.

Marino, C. and Spada, M.M. (2017). Dysfunctional cognitions in online gaming and internet gaming disorder: A narrative review and new classification. Current Addiction Reports, 4, 308-16.

Marino, C., Gini, G., Vieno, A., Spada, M.M. (2018). The associations between proble- matic Facebook use, psychological distress and well-being among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta- analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 226, 274-81.

Nikèeviæ, A.V. and Spada, M.M. (2010). Metacognitions about smoking: a prelimi- nary investigation. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 17(6), 536-42.

Nikhita, C.S., Jadhav, P.R., Ajinkya, S.A. (2015). Prevalence of mobile phone depen- dence in secondary school adolescents. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 9(11),VC06.

Panova, T., Lleras, A. (2016). Avoidance or boredom: Negative mental health outcomes associated with use of Information and Communication Technologies depend on users’ motivations. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 249-58.

Park, S.Y., Yang, S., Shin, C.S., Jang, H., Park, S.Y. (2019). Long-term symptoms of mobile phone use on mobile phone addiction and depression among Korean adolescents. In- ternational Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 16(19), 3584.

Riley, B. (2014). Experiential avoidance mediates the association between thought suppression and mindfulness with problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Studies, 30, 163-71.

Sahu, M., Gandhi, S., Sharma, M.K. (2019). Mobile phone addiction among children and adolescents: A systematic review. Journal of Addictions Nursing, 30(4), 261-8.

Sohn, S.Y., Rees, P., Wildridge, B., Kalk, N.J., Carter, B. (2019). Prevalence of problematic smartphone usage and associated mental health outcomes amongst children and young people: a systematic review, meta-analysis and GRADE of the evidence. BMC psychi- atry, 19(1), 1-0.

Spada, M.M., Caselli, G., Wells, A. A. (2013). Triphasic metacognitive formulation of problem drinking. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 20(6), 494-500.

Spada, M.M., Caselli, G., Wells, A. (2009). Metacognitions as a predictor of drinking status and level of alcohol use following CBT in problem drinkers: A prospective study. Be- havior Research and Therapy, 47(10), 882-6.

Spada, M.M., Giustina, L., Rolandi, S., Fernie, B.A., Caselli, G. (2015). Profiling metacog- nition in gambling disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(5), 614-22.

Spada, M.M., Langston, B., Nikèeviæ, A.V., Moneta, G.B. (2008). The role of metacogni- tions in problematic Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(5), 2325-35.

Yavuz, M., Altan, B., Bayrak, B., Gündüz, M., Bolat, N. (2019). The relationships between nomophobia, alexithymia and metacognitive problems in an adolescent population. The Turkish Journal of Pediatrics, 61(3), 345- 51.

Journal of Society for Addiction Psychology | Volume 1 | Issue 1 | March 2024 Page 74 - 82